I Read The Best Case for Religion of Our Time

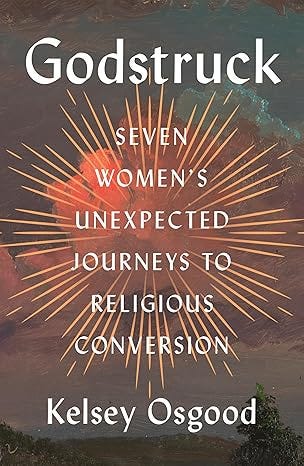

Kelsey Osgood’s latest book, Godstruck, shows why people fall in love with religion

Hello friends, and welcome back after a long Pesach break! This week we have been graced with an excellent guest post by 18Forty’s very own Sruli Fruchter. Sruli is the director of operations of 18Forty and host of its podcast, 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers. A rabbinical student at RIETS, Sruli is also a columnist at the Forward. When not reading, writing, or tweeting about Rav Kook, Sruli enjoys adding books and articles to his ever-growing reading list.

Sruli reviews a book he read over Pesach and argues for the way that religion’s appeal lies in personal experience and emotional connection, rather than logical arguments. It is a moving and eloquent piece that highlights the power of the individual’s journey to faith. Enjoy!

Religion is falling out of style. That’s not my assessment but what the numbers clearly show: 29% of U.S. adults are religiously unaffiliated, rising to 43–44% among 18–34-year-olds. And the trend is accelerating.

Why people leave or reject religion—whether Judaism or otherwise—is anyone’s guess. Some cite the allure of secular life or the clash between Western values and traditional beliefs; others point to religious trauma. As it relates to renewing religious interest, that is a worthwhile conversation to have: Knowing what repels people can revive religious interest. But that is not what Kelsey Osgood chooses to explore. In her latest book, Godstruck: Seven Women’s Unexpected Journeys to Religious Conversion, Osgood wants to know why people choose religion.

The women Osgood follows span various religions—Quakerism, Evangelicalism, Mormonism, Islam, the Amish church, Catholicism, and Judaism. (Osgood herself, an Orthodox Jewish convert, is the seventh subject.) Each chapter centers around a new woman’s story, tracing their fledgling religious interests through their long-winded road to conversion.

Some, like Angela—an Asian-American as devoted to atheism as she was to ethical living—found themselves drawn to religion almost against their will. “I think at some point,” Angela says, “it just felt like I couldn’t imagine not making this part of my life.” Others, like the “spiritually precocious” Orianne, grew up with an innate sense of the Divine, which led her to become a sister of the Daughters of St. Paul.

What binds these women together is their happenstance encounter, engagement, and marriage to faith. Love stories, after all, are always nourishing.

I developed a hypothesis about Godstruck after I finished its first chapter: This is not just a book about religion but a religious book. Osgood both excavates the rich lives of these women with a journalist’s objectivity and speckles her sobered thoughts throughout as an open-hearted friend—all gently nudging the reader to see how God and religion offer what our modern world is ravenous for. And Osgood does so excellently. She invites readers to join these women’s complex religious affairs—their hesitations and doubts, impulsivities and excitement. The messiness of their journeys appeals because of how realistic they seem. (I am thinking of Islamic convert Hana, who moved to Saudi Arabia, struggled in dating, and experimented with Islamic coverings, from the full-bodied niqab to the hair-cloaking hijab.) Reading about people reinventing their identities evoked an envy of admiration in me. It left me feeling profoundly inspired. That is the gift Osgood presents us.

In a word, Godstruck is making the best case for religion in our times.

The conservative New York Times columnist Ross Douthat’ latest book, Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious, is self-explanatory by its title alone. While I did not read the book (and feel embarrassed to even mention it), George Packer of The Atlantic did, and one paragraph of his review struck me:

Douthat guides the reader through the science toward God with a gentle but insistent intellectualism that leaves this nonbeliever wanting less reason and more inspiration. I can’t follow him into his Middle Earth kingdom of angels, demons, and elves just because a book he’s read shows that a universe in which life is possible has a one in 10-to-the-120th-power chance of being random. We don’t fall in love because someone has made a plausible case for being great together. Some mysteries neither reason nor religion can explain.

I will resist commenting specifically about Douthat’s book (because, again, I did not read it), but Packer’s critique resonates with me. Though I grew up Modern Orthodox, my spirit was really churned in my gap year in Israel at Yeshivat Orayta. My own religious growth (read: “flipping out”) did not develop because I heard a “plausible case” presented for it. I instead think back to moments when I caught glimmers of God—Friday night prayer under Jerusalem’s violet sky, desert nights illuminated by distant sparkles, silent walks in a forest drenched in serenity.

Human life resists the strictures of rationalism; so few things in life abide by what ought to be or what makes sense. Why fall in love, or lose yourself in sunsets, or blow out birthday candles surrounded by friends, or open yourself up to the magical quality of religious life? Rationalism suggests that our beliefs and choices follow from a set of axioms that develop by principles into what we call religion, but logic is not what moves hearts.

I am not religious because it makes sense. I am religious because I love God and I believe in religion’s worth and validity. Pulling out a whiteboard to persuade me with Pascal’s wager or Aristotelian proofs only stuns me into repulsion. Living with God, as William James writes in The Varieties of Religious Experience, means living with “a higher kind of inner excitement” that calls one into all of life’s richness. Experiencing that is enough to convince me of it. And I think that is precisely what the people of today are searching for: a faith that convinces them by how they experience it.

The iconoclastic thinker Rabbi Shimon Gershon Rosenberg, known as “Rav Shagar,” wrote about the ineffable quality of his faith in Faith Shattered and Restored:

And truly, my faith is mystical; it is a wordless, letterless faith. It is my lot to believe without telling others … that I believe, much as the kabbalists cleaved to the Almighty with ovanta deliba, “the understanding of the heart.” This psychological technique or practice precedes language and grants it its vitality. In its second phase, belief manifests as a life of faith. It is compelled to function in a world of duality, and if I overlook its origins in the Real (for instance, by trying to demonstrate its objective truth), I destroy it.

Sometimes we are so bent on grasping everything with our human minds, which philosopher after philosopher has acknowledged is inherently limited, that we taint the beauties of life that evade our senses: emotions, stories, dreams, selfhood.

What Osgood offers through her luminous writing and vulnerable storytelling is an intimate view of the spiritual stirrings that lead people to faith. To read Godstruck and follow these women’s stories with Osgood as your guide is to enter into a doorway that leads you to the Divine. Osgood’s own story is peppered throughout the book, culminating in the final chapter in which she recounts her relationship with the “Divine Feminine.” Her journey is profoundly admirable.

If there were ever a question as to how we can save religion from its death rattle in the modern day, Osgood offers an answer. She shows us that the case for religion is best made with feeling, not logic; by demonstration, not persuasion; with experience, not intellect. The best case is no case at all.

What did you read over Shabbos?

A shared selection of Shabbos reads

>>>Sruli reviews a book he read over Pesach and argues for the way that religion’s appeal lies in personal experience and emotional connection, rather than logical arguments.

Isn't this an argument for the enjoyment and entertainment and fulfillment value of religion?

If someone asks you why you waste money going to the movie theater for $25pp instead of sitting on your couch with your loved one(s) and renting it on streaming for $2.99, you can respond, "because money isn't everything. Experience has value and everyone should be free to pay for the things they find valuable." And I would agree. Which is why discussing the personal experience and emotional connection derived from expending tremendous time, effort and money is a discussion about desire and taste. If you want to go out to dinner and spend $328 on something you could have stayed home and made yourself for $24, that would not be a valid attack unless the framework is efficacy or economy.

But religion is not about experience and emotions. That's how people feel, but it's how they feel about things that they claim are true. I have no problem with you eating your matzah-horseradish sandwich while leaning or lighting the menorah because it's your cherished culture. But to say that because it's your cherished culture, therefore it's true, that's faulty reasoning.

Of course the basis for religion is personal experience and emotional connection; we don't need a book to argue that, unless the book starts off by saying: "there's no good reason to think any of this is true, but let's discuss how much fulfillment you can derive." And if the argument makes sense to you, then expenditures (in time, effort and money in the form of buying tzitzis and paying private school tuition and giving the mikva lady $40 and paying $9/lb for Empire chicken instead of $3 for Tyson chicken) cannot be argued against, other than from an economical perspective. I could try to convince you that you don't need those expensive dinners out and those expensive clothes and you can either be convinced and save money and stay home and make your own food for much cheaper, or you can disagree.

>>>Some, like Angela—an Asian-American as devoted to atheism as she was to ethical living—found themselves drawn to religion almost against their will. “I think at some point,” Angela says, “it just felt like I couldn’t imagine not making this part of my life.” Others, like the “spiritually precocious” Orianne, grew up with an innate sense of the Divine, which led her to become a sister of the Daughters of St. Paul. What binds these women together is their happenstance encounter, engagement, and marriage to faith. Love stories, after all, are always nourishing.

>>>In a word, Godstruck is making the best case for religion in our times.

It seems clear to me that this post is making my point. The best case...the only case...for religion are stories like this. That people want fulfillment and they want to feel connected. They feel something is missing in their lives. And all of that is fine. But how could you possibly suggest that stories about 7 different conflicting and largely mutually exclusive views (Quakerism, Evangelicalism, Mormonism, Islam, the Amish church, Catholicism, and Judaism) could promote a unified idea?

Hitchens and Harris highlight this failure when they speak of how religion is a suitcase term. To say that Mormonism and Catholicism and Islam and Judaism are all religions is to say that chess and badminton and tai boxing are all sports. What is the value of referring to them all in the same category, Harris asks, when there is hardly anything linking these various sports other than breathing? It's a false alignment being proposed here, and it's so obvious to anyone who considers it for more than a moment. It's only beautiful to talk about 7 women's paths to personal connection and emotional fulfillment if you don't ask them about what each on thinks about the other 6 women and their necessarily false journeys. According to Wikipedia, Islam would maintain this about Mormonism:

"LDS Christianity asserts that the Godhead is made up of three distinct "beings", Heavenly Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Ghost so united with one purpose as to be indistinguishable. Furthermore, its doctrine of Eternal Progression asserts that God was once a man, and that humans may become gods themselves. All of this is emphatically rejected by Islam, which views these doctrines as polytheistic, sinful, and idolatrous, totally the opposite to the revelation of the Quran and the teachings of Muhammad, the final prophet of Islam."

I won't bother going through all the other conflicts between the 7 religions referenced, but suffice it to say that Hitchens and Harris make a lot of sense here and Osgood seems to be very confused. It's not that emotions do not matter, but it's that they do not matter for the assessment of truth when you're assessing the truth.

If doesn't matter how much you want a sandwich...if you don't have bread, you can't make a sandwich.

>>>I can’t follow him into his Middle Earth kingdom of angels, demons, and elves just because a book he’s read shows that a universe in which life is possible has a one in 10-to-the-120th-power chance of being random

George Packer clearly doesn't understand evolution. It's not random, just unguided, and the difference is not trivial.

>>>I am not religious because it makes sense. I am religious because I love God and I believe in religion’s worth and validity

Can you elaborate on this, please? You say you love someone, but how do you know he exists? You say you believe in religion's worth (which is immaterial) but also that it is valid. Can you please explain what you mean by this and why?

>>>Kelsey Osgood’s latest book, Godstruck, shows why people fall in love with religion

Just because people do something doesn't mean they have good reason to do so.